Software organizations are swirling masses of ongoing activity, constantly flowing in an endless stream of decision and action. As long as they are alive, they evolve, adapting themselves to fit into the larger environment while adapting the environment itself toward more favorable conditions.

There is inevitable drift in the organization-environment coupling. There is inevitable degradation of internal coherence. We experience these drifts when projects feel stuck, stalled, or misguided. We sense them when strategy seems disconnected from conditions of the world around us. If we don't feel it, it's early in the project or team lifecycle, our scope of awareness is safely narrow, or we're working with extremely skilled talkers.

When we do feel it, we can choose to try and shift things for the better. It takes care, effort, and often a dogged persistence: the organization has evolved to do what it is currently doing, after all. If change is possible, finding a foothold and gaining leverage for change is less a matter of what we do directly, more a matter of where we can intervene.

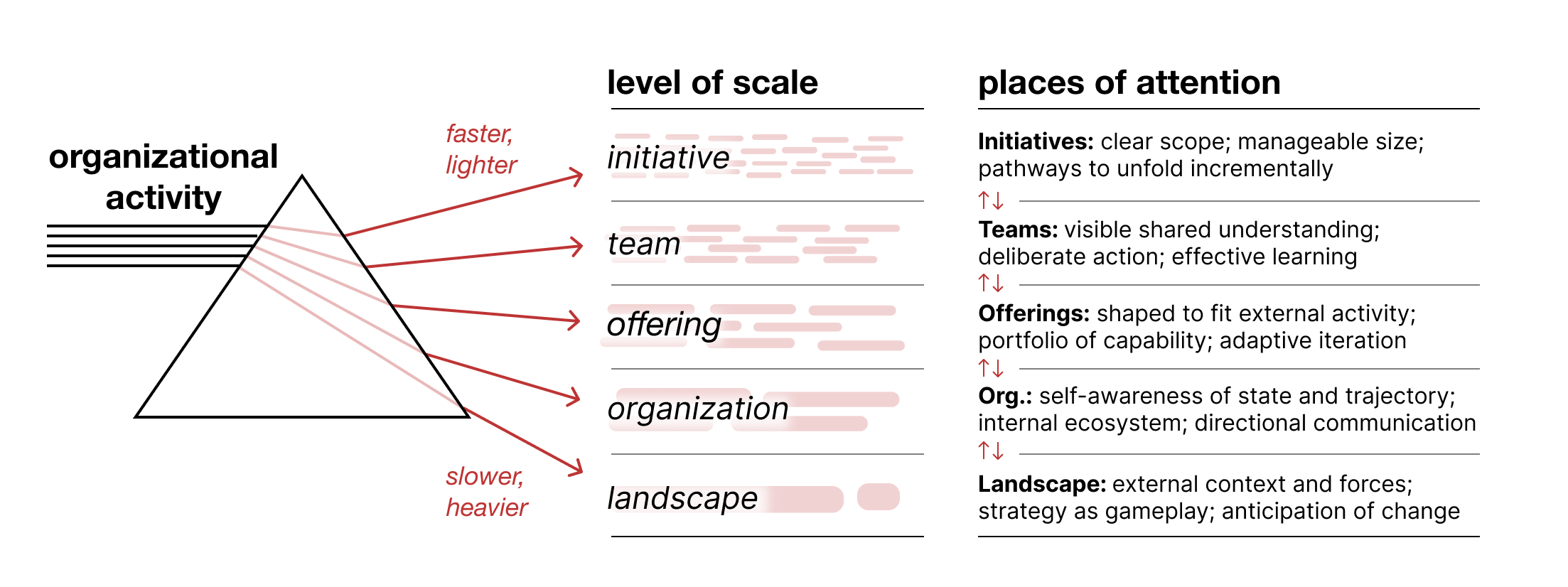

I'm still developing the levels of scale that have emerged over the course of Loops and Cycles. They're shifting into a shorthand framework for the places where problem signs appear, and where we can look to intervene. In Alexandrian terms, the places of repair, and in my experience, the places where problems tend to emerge.

And problems do emerge. They're a matter of course when people build things together. They're a natural consequence of change and growth. Intent evolves, expectations change, priorities shift, the environment moves, and awareness of the situation becomes fragmented.

All of this is a long way of saying: maintenance is required. Somebody needs to control the weeds, prune the vines, treat the mold and mildew in the garden. It's easy to focus so tightly on what the organization is trying to achieve, that the health and capability of the organization itself are overlooked. Each level of scale above is a place of repair; a place of continuous attention where some amount of effort must be invested to correct the inevitable drift and reinforce coherence.

Most of the industry literature that got us here — design, product, research, and organizational writing — assumes that things can and probably will go according to plan. It positions how things should be and potentially could be, without addressing the actual context of the organization, products, and teams in question. It's as if current infrastructure, past commitments, and individuals' prior experiences don't exist.

There is a parallel discussion in architecture. In their book The Discovery of Architecture, Ashish Ganju and Narendra Dengle discuss the concept of "maintenance as renewal." They say:

Once built the physical object is subject to entropy and will decay; hence a continuous activity of maintenance is essential to renew and extend its life/usefulness so that it remains an asset to the community. (p.5)

And later, continue:

The construction of a building is only one phase in its life. Once complete and as the building ages, its behaviour also matures. This behaviour is expressed in the language of architecture, and this is most evident in the task of renewal, whether on a daily basis or seasonal or annual maintenance. (p.39)

That a building will need maintenance and repair is self-evident. (Though in a more modern approach to architecture, that appears to be less true.) I'd argue it's just the same for any given organization. So much is written about building the organization and building product and growing everything. Very little is focused on the recurring process of maintenance and repair. Ganju and Dengle continue: the very act of repeated maintenance is a source of wisdom and a place of embodied understanding.

At its simplest we note that repeated action can result in increasing knowledge about the action. At first this may be evident only as increasing skill, but the information that gets stored in the memory is the root of learning. (p.49)

Where, in our organizations right now, is that skill and tacit knowledge? And who knows how to keep things on track, correct the drift, increase coherence, identify promising new places of growth, and help them emerge in light of inevitable and often-predictable obstacles? Those of us in the product development organization are primarily technicians focused on producing or organizing our functional expertise — the engineering, designing, product-managing, or researching of the thing. Who is focused on maintaining and repairing how everything fits together?

Other things of note

- I've been tracking books-read on Goodreads for quite some time: 997 are complete, and I'm currently reading three: The Beak of the Finch, Who's Afraid of Romanee-Conti?, and Seeing What Others Don't. After I reach 1,000 logged books, I'll look back and write about some favorites and recommendations here.

- I recently learned about 99% Invisible's breakdown of Caro's Power Broker. It's a read-along podcast series, and a lovely way to explore, review, or guide your reading through the meticulously crafted history of Moses' acquisition and use of real political power in New York City.

![Maintenance Required [LC30]](/content/images/size/w100/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-01-at-17.23.00-1.png)

![Seeding a Product Framework [LC31]](/content/images/size/w100/2025/12/full-framework-thumb--1--1.png)

![Vineyard and Complexity [LC29]](/content/images/size/w100/2025/08/marco-vines-1.png)