If you've been following Loops and Cycles already, our theme is familiar: it's hard for people to work together and build good things. When we build products and services that run on software — when their reality occurs in places and on devices outside of our control — it's especially hard: what we shape and its use in practice are not easily observed or adapted.

Sometime around 2014, I believed that depicting experience was the answer. We worked with stories or sequential depictions; I wanted to capture the moment of experience and see how it was structured. If we could define and optimize for an ideal end-user experience — whatever happened in the black box — the strategy to deliver that experience and the flow of work would become obvious; operational problems would sort themselves out!

My academic naivety remained for longer than I care to admit: the mind was full of ideal theory, the body liked the determinate correctness of numerically-graded practice.

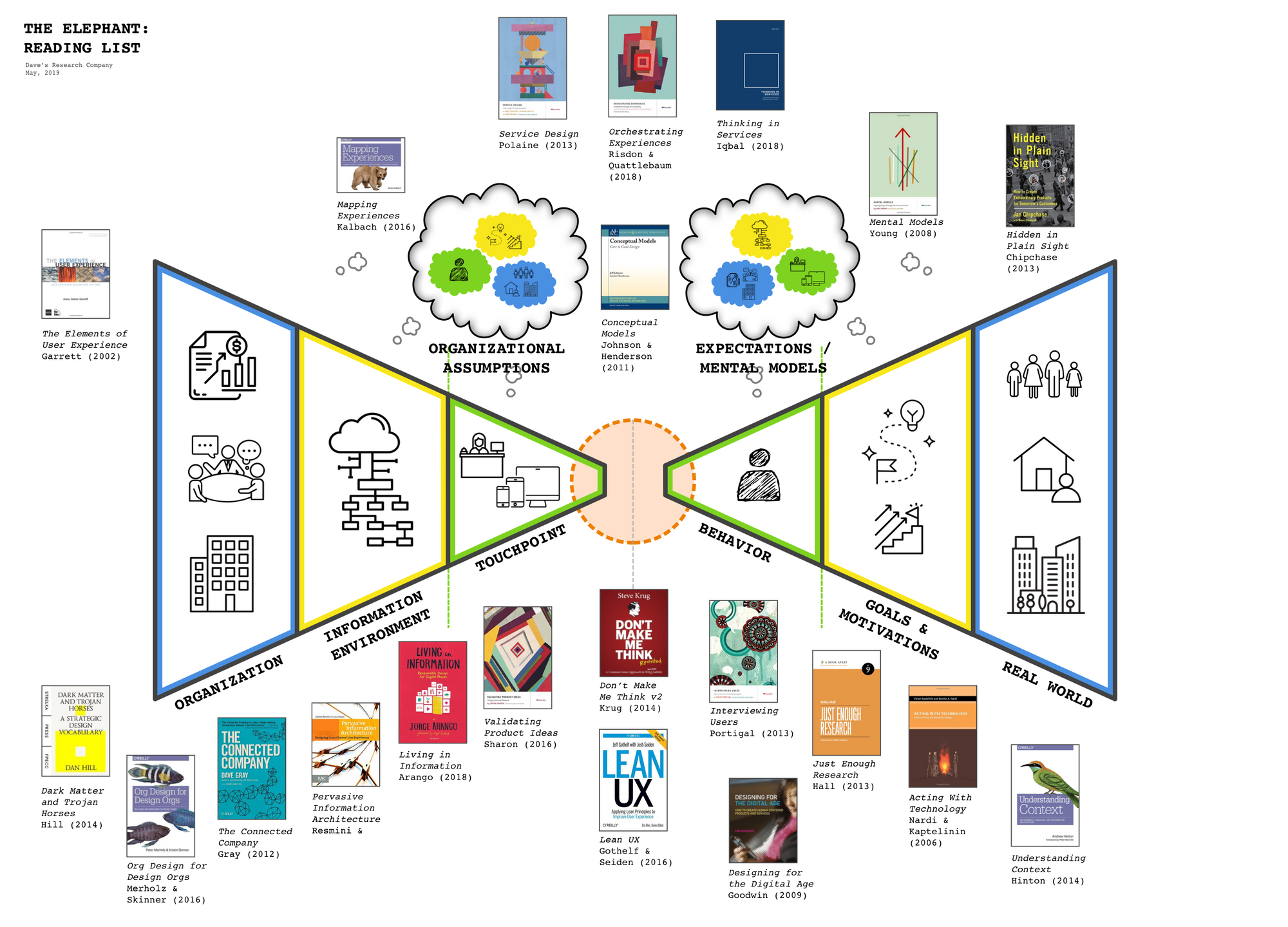

For years, I kept reading and sketching on the structure of an experience as I encountered work situations I couldn't explain. I pulled everything I'd been reading from my prior explorations into a model I called "the elephant" and tried to show how all the pieces I'd read fit together. I felt, at the time, as if I'd really solved a problem by drawing this picture.

I spoke on that model in 2019 at User Research London (see slides — there are some real bangers, e.g., 50/51, 76–79 ). I found it could explain basic phenomena, but also that it wasn't actionable for others. It served more as a personal totem I carried by virtue of having drawn it for myself, a reminder of what to think through and which tools or frameworks from reading I could pull on in consulting situations.

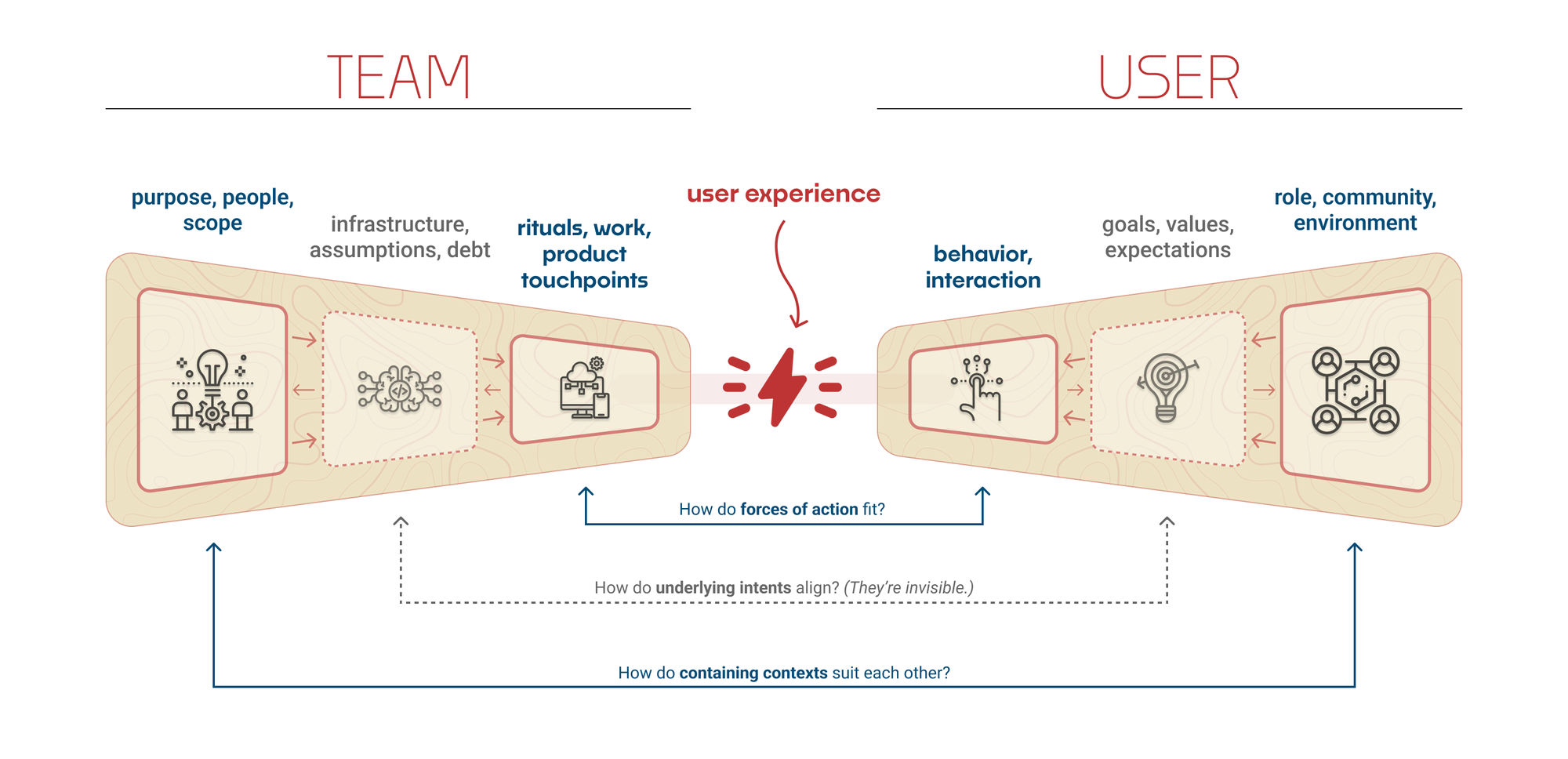

Early in 2024, I revisited the same model, simplifying and re-articulating it as The Structure of User Experience. But the problem remained: it's neither operational nor tractable.

The focus on the lightning bolt of experience, a hangover from 10 years ago, means it does not appropriately emphasize the structure at play in a given situation. An abstract depiction of an experience doesn't help solve problems. It takes keen-eyed view of what is happening right now, for a specific team, working with a specific offering, in a specific organization, to unlock the path forward.

What I was after, I realized, was something more like a Wardley Map or an Estuarine Map, the kind of tool that offers a canvas for us to articulate the specific concerns we're discussing, moving from stories about what's happening with the work to a concrete depiction. A way to unlock new opportunities for stalled teams and their entangled product problems.

This summer, I wrote, and drew, and sketched. I wanted to turn the model into a sensibility for solving the problems I encountered in consulting — problems of change, adaptation, strategy, intent, and operation.

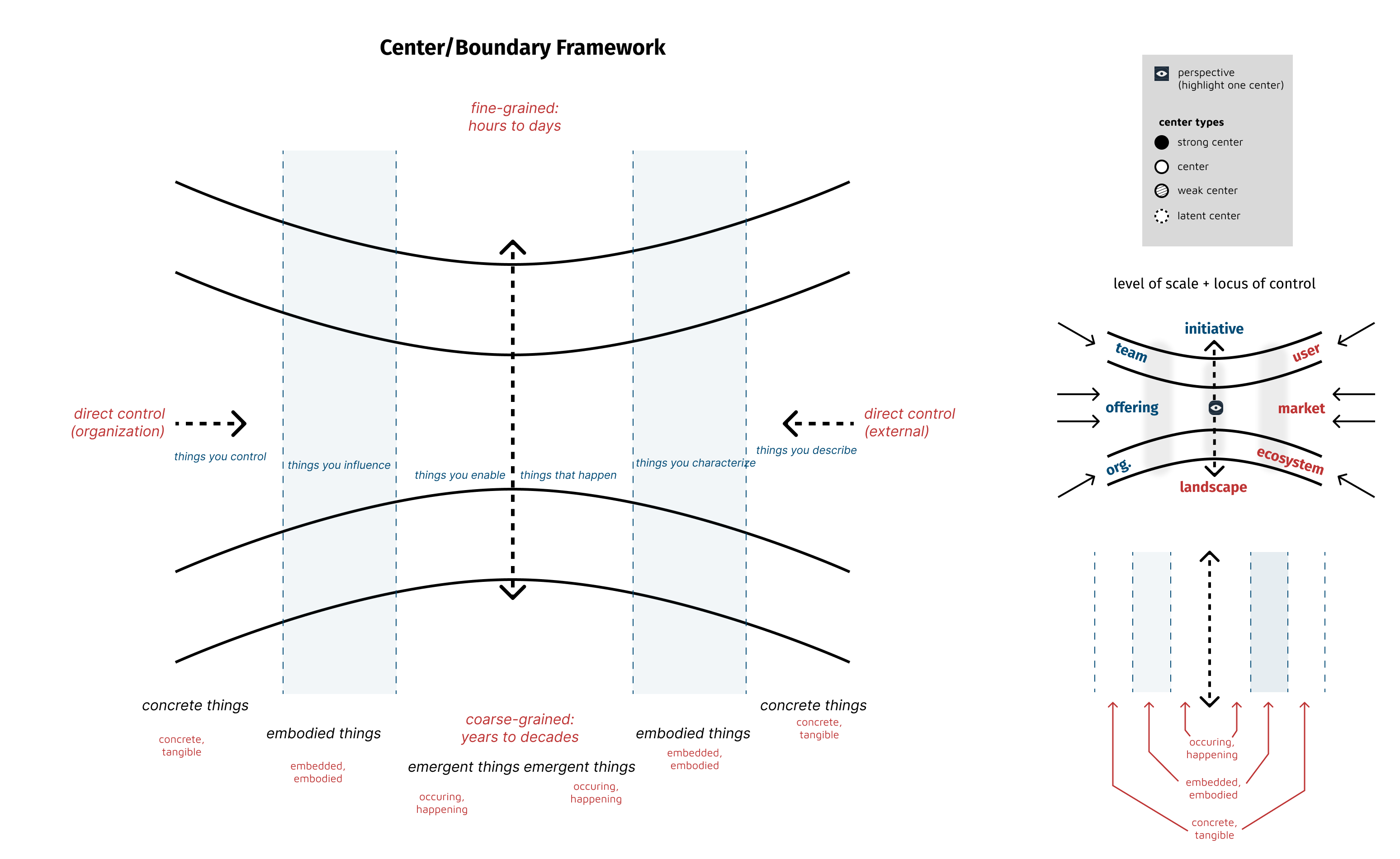

It appears complicated, but only a few core ideas are embedded into its shape: a pace-layer-inspired Y-axis, a locus-of-control X-axis, and a typology of elements based on how to handle them.

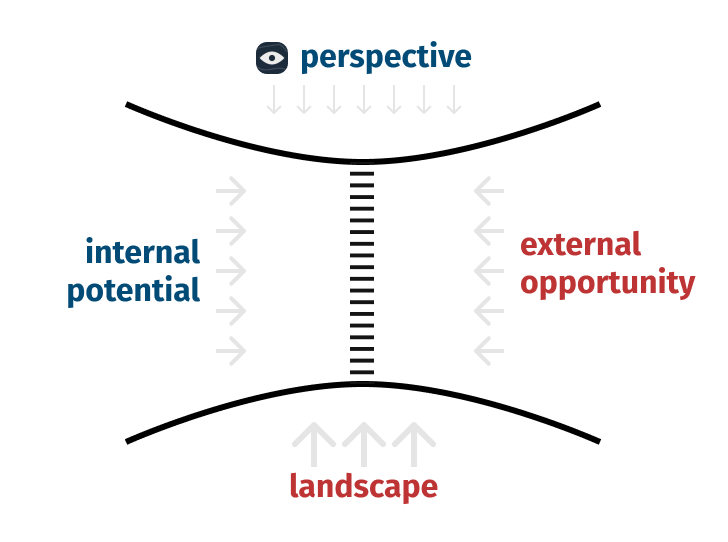

Following Dave Snowden's table napkin test —"any framework or model that can’t be drawn on a table napkin from memory has little utility" — we can condense all of the above into the simple frame below.

The basic thesis is one of awareness. Teams will work themselves into fixed frames and tight perspectives that become self-limiting. They will fail to anticipate predictable events at timescales outside of their immediate concern. And leaders will misdiagnose all of this, taking dramatic, large-scale actions that are destined to fail, because they can't address the real structural faults at the right timescale and level of granularity. Much of my consulting begins as a research question; an outsized portion of the value simply comes from refreshing and reframing an answer to, "what is going on right now?"

This is the seed of our exploration for season 3. A framework is interesting, but what's more important is what it's trying to say about the world.

We'll assume no prior knowledge, then try to build out the implications of this view and show how it helps unravel the predictable kinds of problems that product teams encounter.

Other things of note:

- See Wardley and Snowden on The Complexity Lounge (youtube): two curmudgeons talking with (and past) each other about the problems and challenges of the current, LLM-specific interpretation of AI. It's dense, interesting, and frustrating — try listening to the first hour, keep going if you're hooked.

Until next time—

This is Loops and Cycles, a mailing list exploring how we work together and make good things.

![Seeding a Product Framework [LC31]](/content/images/size/w100/2025/12/full-framework-thumb--1--1.png)

![Maintenance Required [LC30]](/content/images/size/w100/2025/09/Screenshot-2025-09-01-at-17.23.00-1.png)

![Vineyard and Complexity [LC29]](/content/images/size/w100/2025/08/marco-vines-1.png)