What does it take to establish an influential research function in a modern product organization? We need to learn how to see where the action and leverage lie outside of our research program itself, making moves that root our activities into the larger landscape, iteratively and adaptively.

The Challenge and Our Purpose

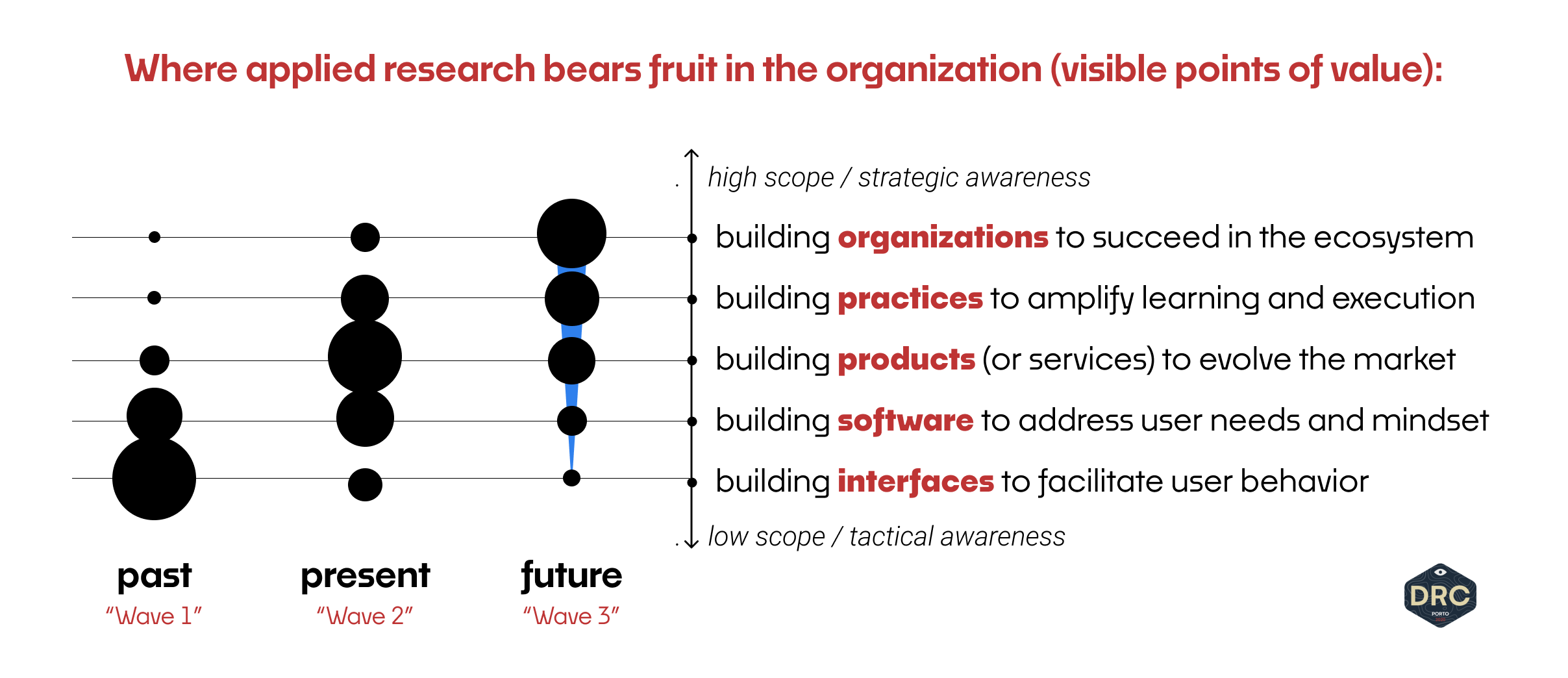

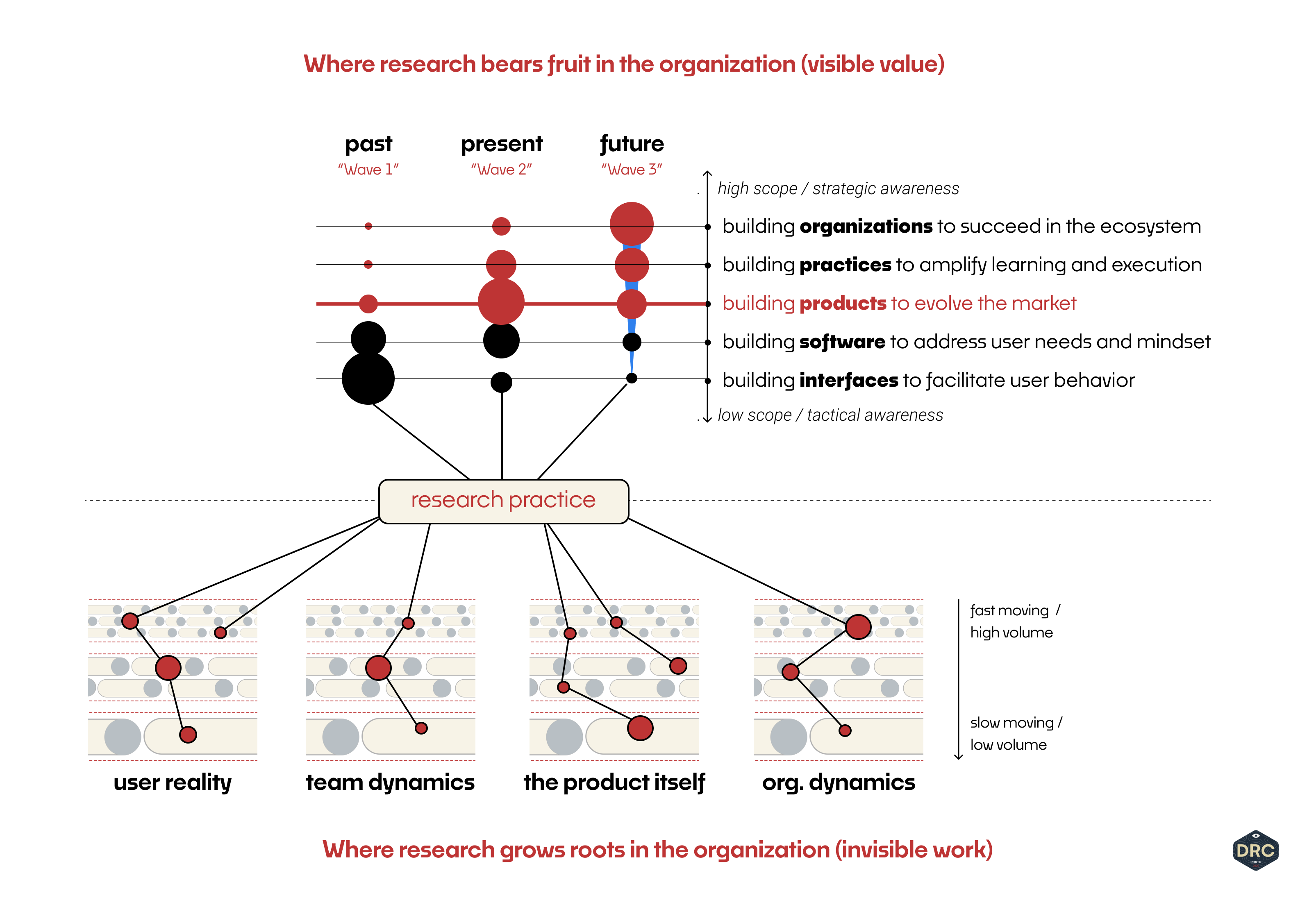

In last month’s Three Waves, I tried to characterize the change in research from UX and Product work (Wave 2) to Strategic and Business work (Wave 3) as a kind of phase shift. What’s more important, though, than trying to isolate a specific mode of research practice is to see that research practice as a living footprint of activity that bears fruit across a range of organizational scales from tactical to strategic.

In every product organization, some team or individual is attempting to carry out work at each level of strategic scale: from front-end interface systems up through higher-order organizational strategy. Formal research practitioners may be staffed and focused on any of these levels — or, just as likely, they may not. Regardless, there are learning–execution–feedback cycles that already exist at each level. These cycles in each level of scale are the primary places where research delivers value in an organization.

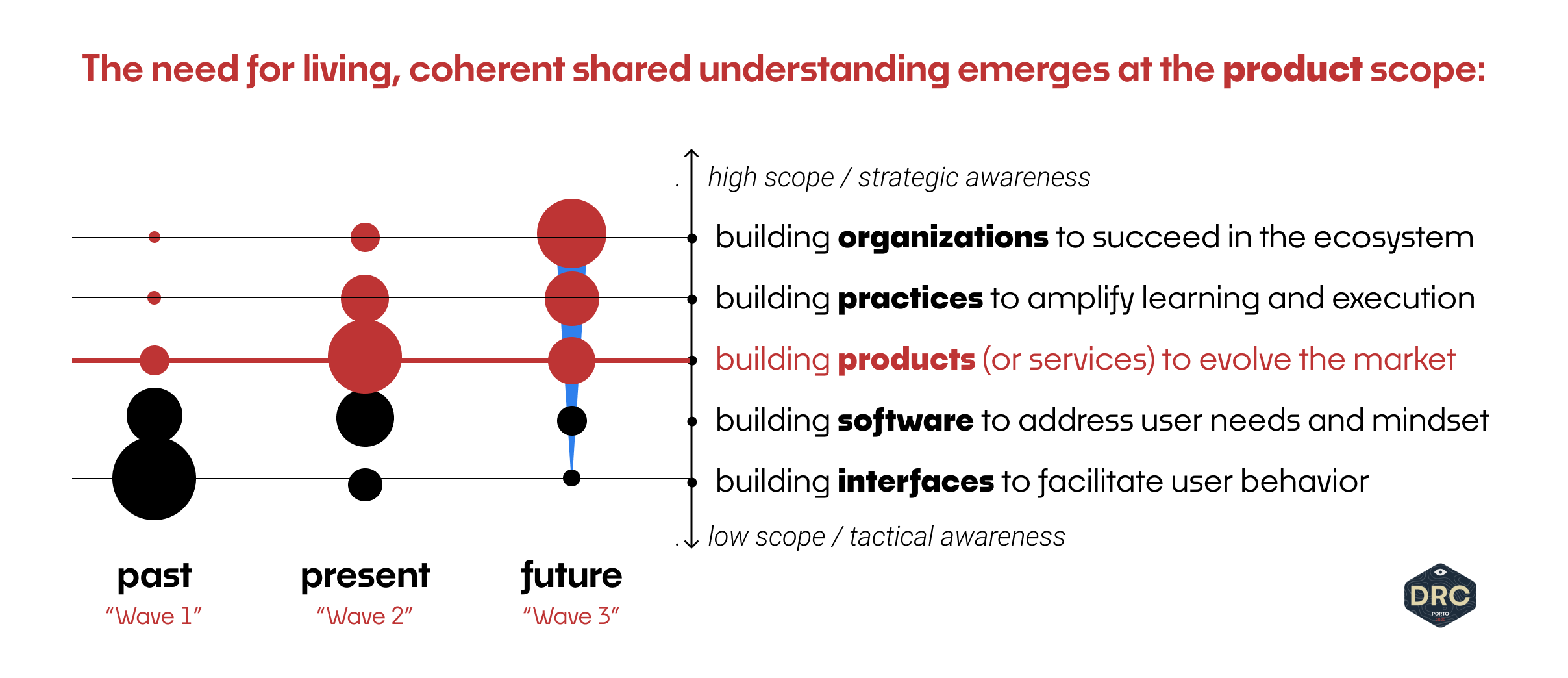

Most of our work delivers in the product level right now (previously, Wave 2). Here is where we grapple with the most interesting challenge in establishing research. By the time an organization decides to invest in research capability, it’s likely to be product-led, or at the least design-forward. These kinds of organizations can carry out the basic operations of research on their own, especially with the help of modern software vendors and off-the-shelf practices. Product-led teams are more likely to have existing insight loops that move at a much faster pace than traditional research structures do, like Teresa Torres’ continuous discovery practices designed to arm product teams with actionable on-demand insight.

Research practices growing in modern organizations may not own short-cycle customer interviews, but to be deeply effective, they must build a fabric of shared understanding that connects short-cycle learning to a well-structured larger perspective. In the product scope, and each lower scope, generating insight is easier than ever; coordinating a coherent shared understanding — up and down the levels of strategic scale — is a new and growing demand.

Long-cycle modes of work disconnect researchers from the very day-to-day context the work will be activated in, and teams’ fast-moving understanding of context may shift outside the scope of a carefully planned research project. Understanding where our current footprint of practice sits, and where the organization is already generating insight, helps us understand the nature of the challenge we face in establishing research.

The fact that insight may be generated independently at each level of scale points to a new kind of continuous shared intelligence challenge that research is well-positioned to address.This is a massive and interesting challenge we’ll investigate more thoroughly in the future.

Even in the face of this new challenge, our approach forward remains the same: we start by rooting into the organizational practices, knowledge, and execution cycles that already exist. Our aim is to grow our research program, an existing footprint on a real organization's product practices, into a healthy part of that system with a clear path up the ladder of strategic complexity.

Four Places for Adaptive Growth

What do we need to know in order to adapt this specific practice to this specific organization? To get there, we have to work from a more detailed and opinionated point of view about where to focus our effort, and take an iterative perspective on growth. “Adaptive” growth because each of our moves, when well-formed, change the larger environment, and require us to adapt our next moves to that updated landscape.

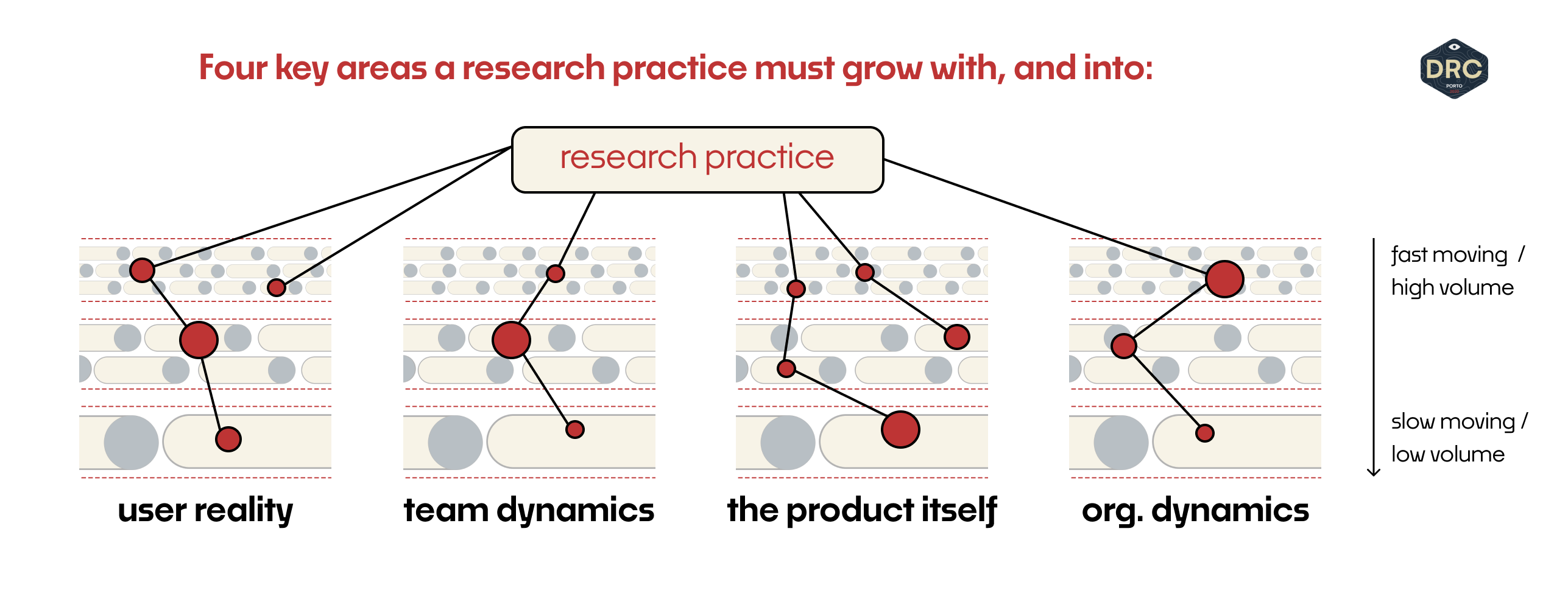

Building out research means doing essential and invisible groundwork in that landscape to allow for the trust, credibility, leverage, and impact a successful program entails. All of that work starts outside the research itself, in four key places:

- In the connection to User Reality

- In product and functional Team Dynamics

- In the actual reality of the Product Itself

- In higher order Organizational Dynamics

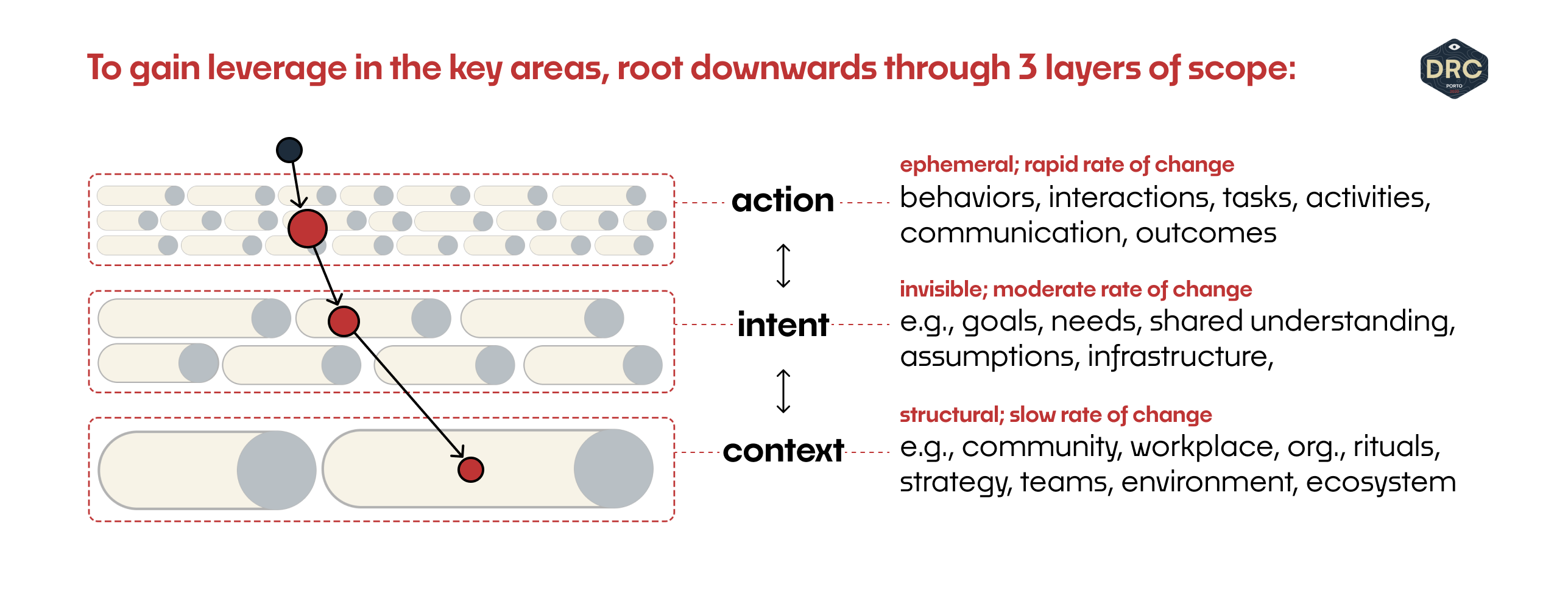

We can imagine each of these areas as the substrate where research grows its roots. This is the work that later enables research to bear fruit in higher orders of strategic complexity. We start by integrating with the fast-moving action-oriented layers, and work our way down into the slower-moving and longer-scale layers.

Any of these four areas is a potential starting point: any of them might offer the right beginning move for a growing research practice. Early on, it’s fair to treat them independently, weighing how they’re connected to ensure that action in one context will actually unlock or unblock new action there, or in the other contexts. We may, for example, need to first visualize the team’s current implicit assumptions about user context by drawing sketchy journey maps based on product capability, before it’s possible or useful to investigate the current-state user journey in the real world.

Over time, with further integration and growing success in each context, the research function generates organizational capital by holding a coherent view that ties all of these contexts together, understanding the implications and dynamics of this larger user-team-product-org system..

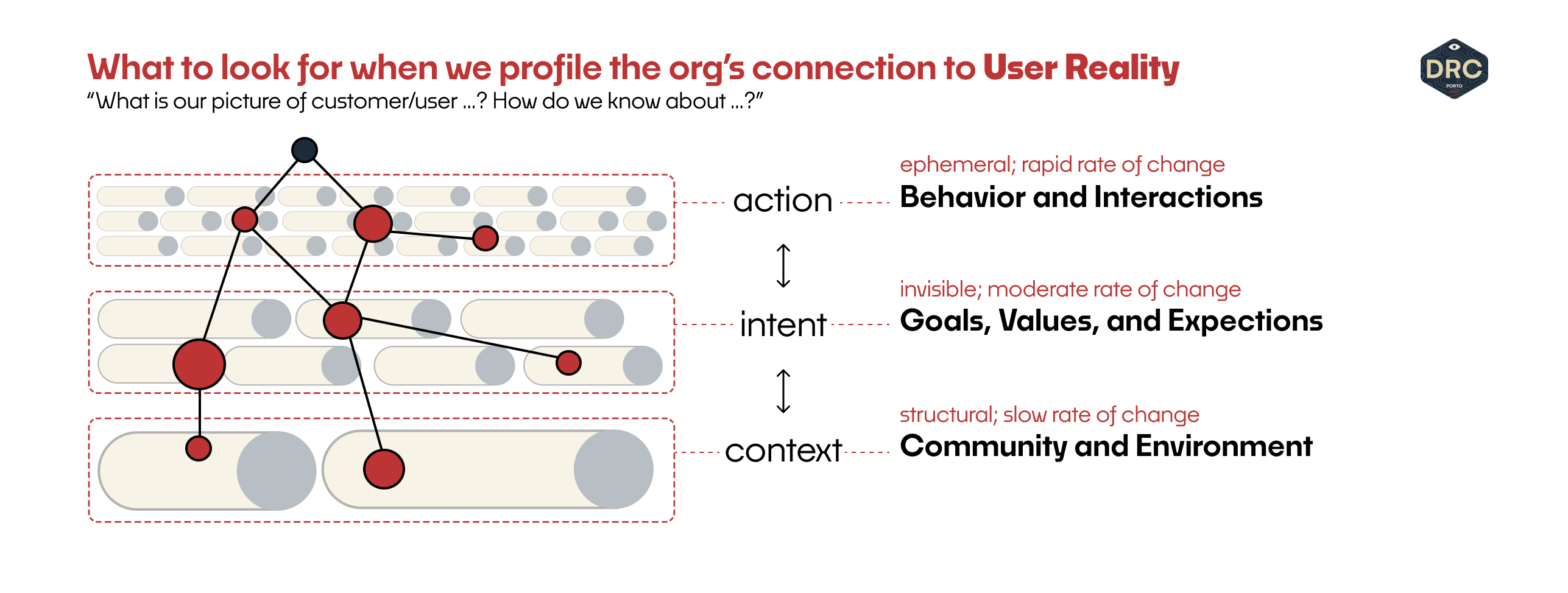

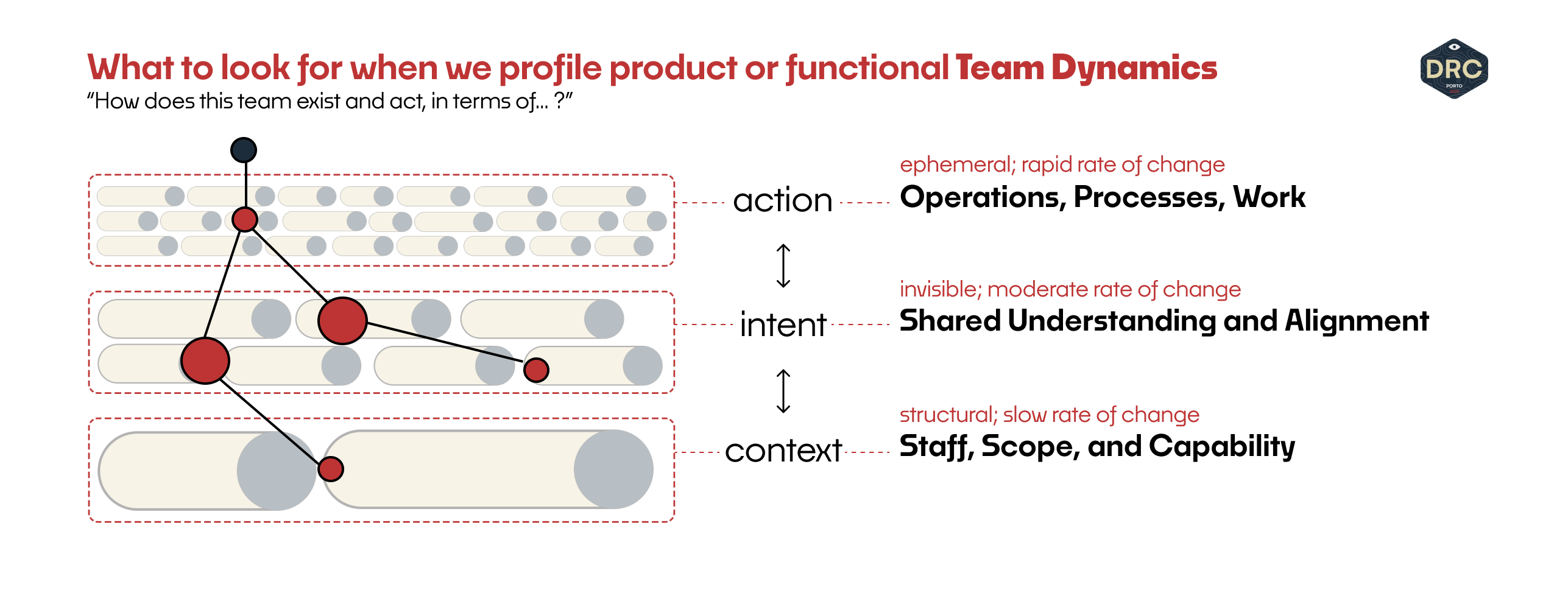

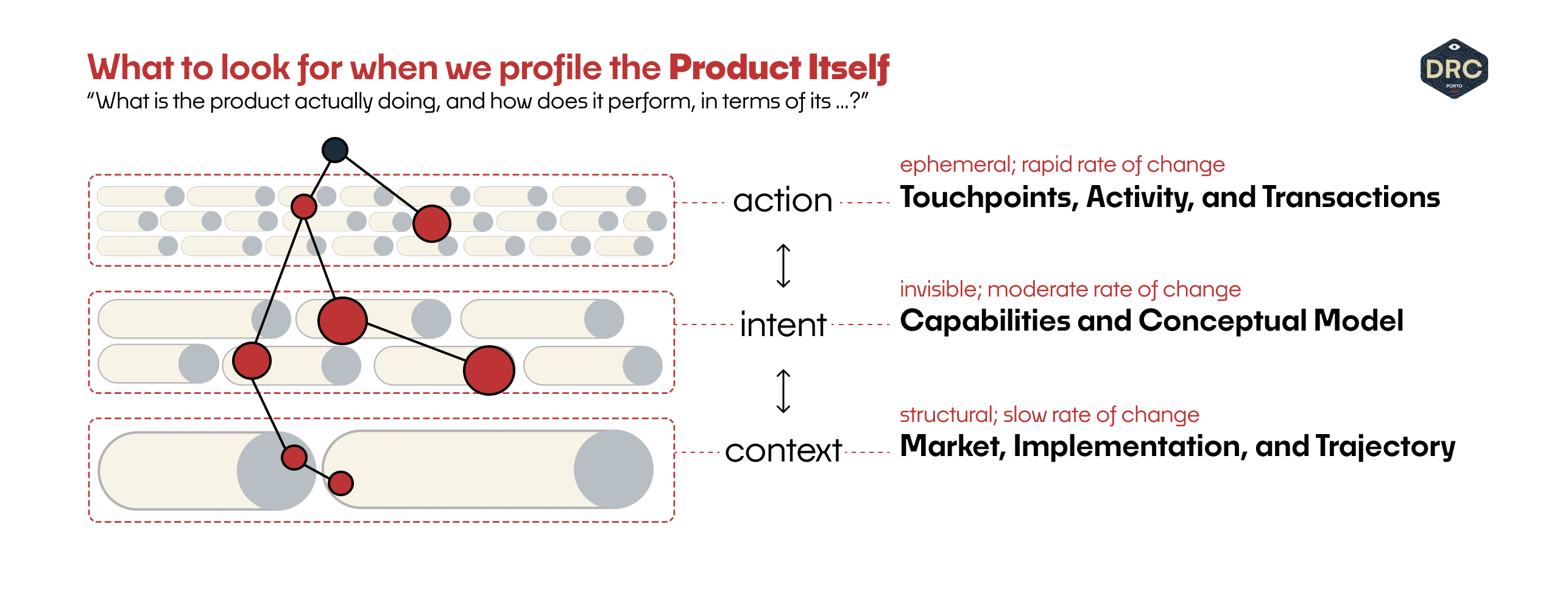

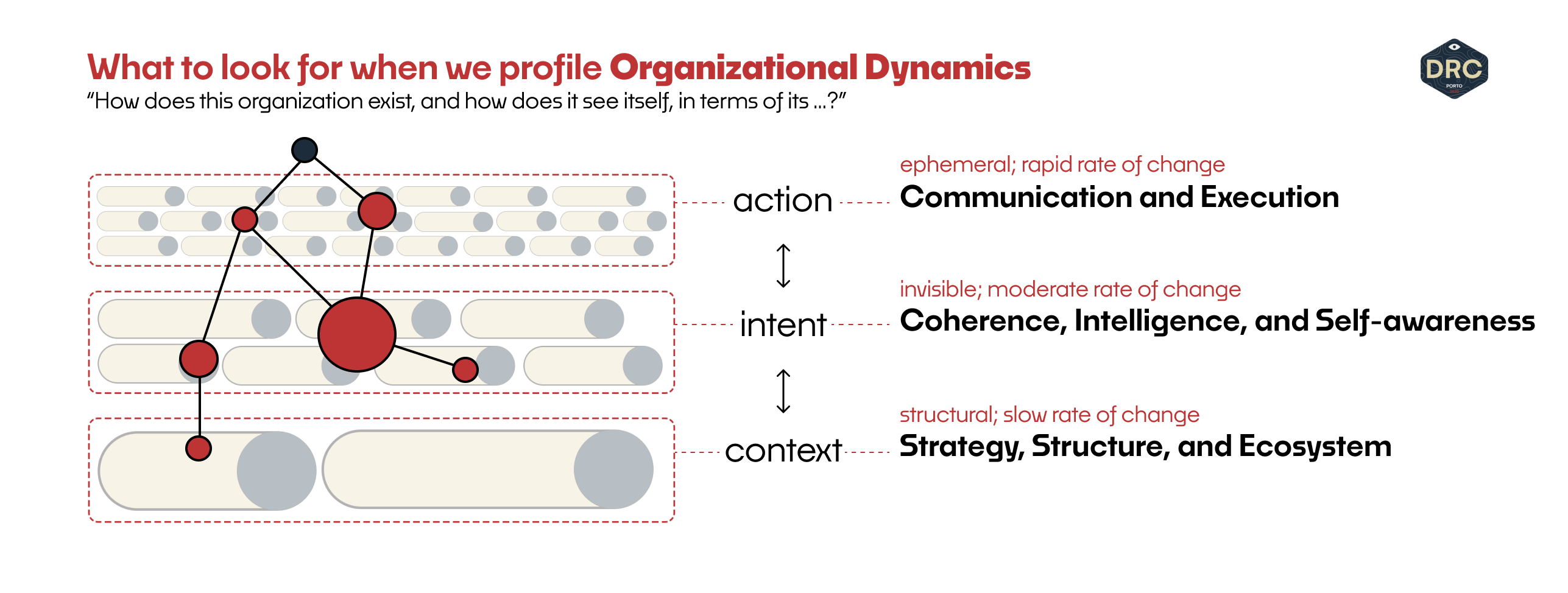

We can view each of the four areas above as a continuum of tactical to strategic layers of change. It’s often the case that the higher, tactical layers — faster-moving and shorter cycles — are much easier to establish a foothold, and they unlock new leverage, action, or integration in the slower, lower layers: from ephemeral action to intent to more strategic and structural context.

Today we’ll take a light dip into each of the four areas. Our goal is a first understanding what those different layers mean in practice, seeing the kinds of things a research leader or practitioner should look for as potential points of leverage and integration.

Area 1: The User Reality

How well-formed, appropriate, and current is the team-or-organization’s understanding of their user context? It’s usually the first place we want to get a hold of as we’re trying to understand the path for growing research in an organization.

While the depth here may be infinite, for any given product scope, there’s a finite surface area of associated user context. The team, product, and organization each support only a certain set of activities or patterns of action; they enable users to accomplish a certain set of specific needs and process flows; they implicitly or explicitly fit into certain kinds of social groups, communities, workplaces, and physical environments. How much of that do our partners and colleagues already see?

A sharp researcher with a grounding in product should be able to form, quite quickly, a rough-idea outline of which user journeys, goals, scenarios, power structures, and workflows that a product’s existence implies (and depends on.) It’s not a widespread skill: for my own engagements as a consulting researcher, it currently offers one of the best places to start when working with product teams, and even existing research teams. One might call it the fingerspitzengefühl (finger-tip feeling) for research. Friend and fellow consultant Dr. Andrew Muir Wood says, “For me, this is the intuition that is analogous to an old car mechanic knowing where to bang the engine with the spanner. It takes experience, pattern recognition, and confidence”

In general, modern product teams have strong quantitative signals on the layer of action, and implicit or explicit assumptions about the layer of intent, encoded as user needs, opportunities, or jobs to be done. Especially in B2B organizations, those higher order user-role-customer distinctions, power structures, and canonical current-state workflows at the layer of context are extremely important aspects in getting the product right — and are often understood in a hand-wavy and implicit manner.

For this context, nimble naivety is key to finding the crucial product or team assumptions and their connection to actual user context. Weeks or months of fruitful partnership can start with a few conversations and napkin sketches.“It seems like the most important thing we’re doing is supporting this shape of workflow for these kinds of roles… what do we know about them? How do we know?”

Area 2: Team Dynamics

To start understanding the dynamics of a team, we want to look at how that team works— who’s there, how they actually conduct the work, its rhythms, its pace, its rituals, and the content of work or kind of output that any given team has. Team contexts are important to us because we must understand them to chart the path from research activities into product outcomes: the teams we work with are the first place our work moves from theory to practical action.

Especially interesting for us are the threads (or lack thereof) that bind this team to their user reality in the layer of intent: how much of that context are they exposed to, how well do they understand it, and how shared and aligned is that understanding? This is the logical place to profile alongside the user context: the team’s scope and ownership of product along with its ways of working, suggest how their connection to user context should exist, and help us determine where the initial opportunities lie to weave that context more deeply into the team’s shared understanding and their active processes of work.

This is a lens that can be applied to multiple instances of context, but it’s often best to scan quickly and find one place to build depth. Research doesn’t need to grow with all teams all at once: it needs to find the best balance between potential impact and ease of integration into existing cycles. The pacing of a team’s learning and feedback loops, and their introspection and awareness of their work processes help us identify the best potential partners for early research work.

Our goal in understanding team dynamics is to find the right team, or teams, to work with, whose surface area of execution will act as the proving ground for those things that we would ultimately like to see our practice accomplish.

It’s alluring, for example, to try and jump in with the team that’s doing cutting edge and mission-critical work: of course a research mindset could help them accelerate their learning and develop new product more effectively. But the strategic importance of their work has no bearing on whether or not that team will be a good partner. Many “tiger teams” with a clear understanding of their problem and a strong belief in their approach (valid, or otherwise) are particularly poor partners for early research teams. Better, perhaps, to work with a team where it’s clear we can deliver active value in their development cycles, and then hold up an example for other teams to see and say, “we want that, too!”

Area 3: The Product Itself

When we talk about the product itself, we're interested in its current state, what’s actually happening, and how that relates to what various teams or individuals may think is happening. The product context appears straightforward on the surface — what have we built and what is doing out there? — and its role as the ultimate conduit between the user context and team contexts can make it a more difficult place to operate at first. Building fluency in the product context is the doorway to higher-order strategic work.

When we characterize the product itself, we can talk about insight into product performance and user interaction, and we also consider the learning loops built into the product itself that provide us with information about that performance, and information about broader user context.

One of the most interesting places for research to play, here, is at the layer of intent: how well do teams understand what the product as a whole is doing, and where their work fits in? I rarely work in organizations with a well-structured view of their product in the market that helps connect higher-order strategy statements to teams’ work. It’s an unexpected place to build a broader shared understanding that opens doors into more strategic conversations, from a place of childish curiosity: “When we think about the product, it seems like the core advantage we’re building is this… which rests on this major assumption… and implies the market will… — is that how you see what we’re doing here?”

It’s often the case with small organizations or pioneering product teams that the product itself is the team’s primary lens into user context — it’s effective in the short term and forces us to think about what the team is able to learn through the product and prototypes, versus what the team needs to guide its larger direction. This mode of work implies a blind spot in the user reality one step ahead of product and design implementation. The trajectory of what is not-yet-built casts a shadow over the user context that may be an excellent place for research to shine a light.

The product context is broad and multi-faceted, and with its role as a pivot between users and teams. As we look here for useful points of leverage and action, we’re just as likely to find useful moves in the connected user or team contexts as we are to find effective moves that operate in the product context itself.

Area 4: Organizational Dynamics

Finally, when we look into our organizations, we're interested in their composition, their formulation of strategy, the shared view the organization holds of itself and its purpose, and how its teams work together to execute. Communication is key: attend to the various pathways and channels that support work, that drive organizational storytelling, and that form a coordinated awareness of purpose, context, and progress.

The processes and rituals that the organization goes through to coordinate decisions, to build alignment and understanding, ultimately drive product direction. How authority is distributed between the organization, functional departments, and individual groups or teams is a crucial indicator of the structural fault lines research can work on and along.

In profiling the organizational context, we tie all of the other contexts together. We look at the structure of the teams and how they interact from an organizational perspective. The product itself is a living organism, grown and maintained by various teams, and it is the primary experience that users have with the organization. A strong research program will ultimately bind these contexts together through active participation in organizational rituals, processes, and communication channels.

A growing research program can use some of these channels to sense, diagnosis, and drive action in the other three contexts. Our real entry into strategy comes from working towards shared market/ecosystem intelligence at an organizational level, but the path there is multi-pronged and rarely clear from the beginning.

On Making Moves

Thinking through these areas offer a means of rapidly profiling the world of an organization and the tractable research environment as it exists today. It’s not meant to be an academic exercise — we don’t want exhaustive completeness — it’s meant to help us rapidly find the first few points of entry to keep growing the influence and impact of research as a function in the product organization.

Our approach to establishing research is an iterative, adaptive process, because real and meaningful moves will change how things work in those areas. We work with what’s available, finding the best point of leverage to grow roots and make our play, knowing that after that move will we have changed the environment while learning deeply how it works. The state of the landscape will change. We take another scan and see, now, where the next best move lies.

As new areas of opportunity open up, we grow access to larger spheres of strategic conversation, build new perspectives and understanding of external functions, find partners and allies who will amplify our work, change how we understand our own work and what it offers... and on it goes, cycle after cycle...

This is part of an ongoing exploration into research as it co-evolves with product practices and re-integrates into the organization.

For weekly thoughts on the nexus of products-organizations-process-strategy, and updates on larger resources like this, consider joining my newsletter.